The 100,000 challenge

Article

100,000 new opportunities needed in Scotland to head off threat of highest youth unemployment levels since records began

As Scotland’s schools begin to return following the Covid-19 lockdown and as colleges and universities gear up for the next academic year, many young people and their families will be looking ahead to a new term unlike any other before. But for those young people leaving education and looking for work, the jobs market they are stepping into is among the toughest on record. Without question, Scotland – like the UK as a whole – is likely on the brink of a youth unemployment crisis unlike anything we’ve seen before. This crisis requires an urgent and significant response over the coming weeks and months.

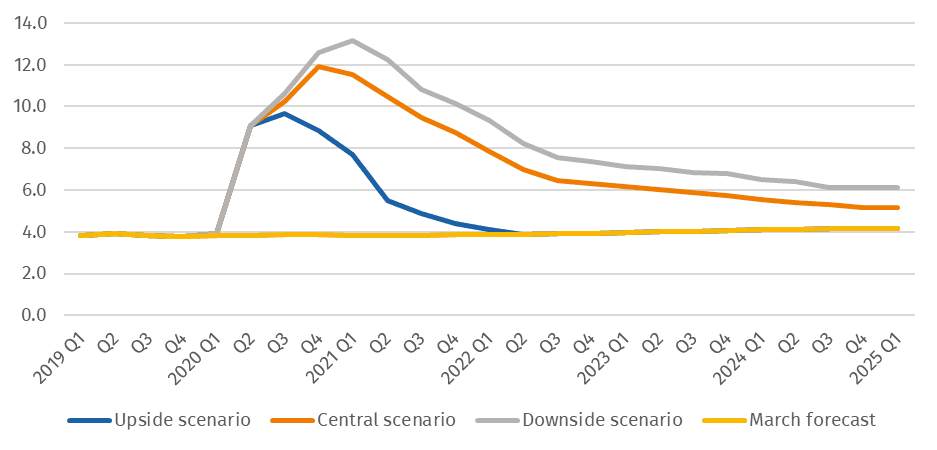

What’s the scale of what we might be facing? While we don’t yet have Scotland forecasts for unemployment, the latest forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) foresee significant increases in unemployment across the UK. If accurate, they would see UK unemployment peak at a staggering 11.9 per cent in the last quarter of 2020, with very little improvement well into next year, and unemployment staying well above pre-crisis levels for years to come (OBR, 2020). This is a huge increase on the 4 per cent unemployment rate going into the Covid-19 crisis and on forecasts as recently as March – just before the pandemic hit the UK. Far from the v-shaped economic “bounce back” initially anticipated by the Bank of England amongst other forecasters (BoE, 2020; HMT, 2020), the OBR’s assessment is now that unemployment is likely to remain considerably higher than pre-crisis levels for as far into the future as 2025. Even worse, this is only the OBR’s central scenario. There remains considerable risk that even this scenario could turn out to be overly optimistic.

Unemployment is projected to peak at 11.9 per cent in the last quarter of the year in the OBR’s central scenario

Source: OBR (2020)

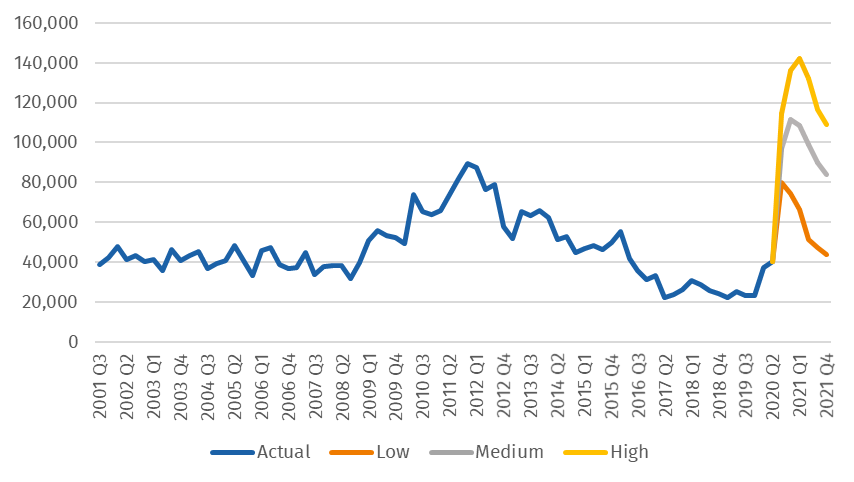

So what does this mean for youth unemployment in Scotland? Below we have outlined a range of projections for youth unemployment in the years ahead. In the absence of Scotland-only data, our central assumption follows historical precedent whereby youth unemployment rises and falls in the same proportions as general unemployment, and Scotland sees around 8.5 per cent of the total youth unemployment across the UK.

This could again, however, be an overly rosy picture. For example, if the OBR’s central scenario proves to be optimistic, and unemployment as a whole is higher than forecast, we would expect youth unemployment to be higher too. Even if this is not the case, there is already considerable evidence that this recession has hit young workers across the UK particularly hard, given the sectors hardest hit by lockdown and ongoing restrictions are also the sectors that employ the highest proportions of young people. On the other hand, forecasts may be pessimistic and, furthermore, young people may not be hardest hit by decisions taken by employers as we move into an expected jobs crisis later this year.

Youth unemployment could exceed 140,000 in a reasonable worst-case scenario

Source: IPPR analysis using OBR 2020, ONS 2020a, ONS 2020b, ONS 2020c, ONS 2020d

In our analysis, in the best-case scenario youth unemployment remains below the peak previous seen in the 2010s, with the numbers of young people unemployed in Scotland staying below 80,000. On the other hand, youth unemployment in Scotland peaks at over 140,000 in a situation where the “downside” OBR forecast is accurate, or where Scotland unemployment increases by more than expected and/or youth unemployment is disproportionately impacted. Our central scenario sees youth unemployment peak at over 100,000, which would see more than one in three of the young workforce in Scotland unemployed – a rate far higher than during the financial crash, and indeed the highest since records began.

The ‘scarring’ effects of unemployment early in a young person’s career are well documented, with reductions in earnings compared to previous cohorts which many young people will not close over the rest of their working lives. There is strong evidence of this effect in recent work looking at the cohort of young people that entered the labour market during the financial crash (Resolution Foundation 2019). This sees significant and lasting economic damage for the young people concerned, but also for the economy as a whole, with large risks to health and wellbeing across Scotland.

The scale of the jobs crisis facing Scotland over the rest of this year and beyond may well be unprecedented. And with it the scale of youth unemployment, and the damage associated to it, could be unparalleled. We must therefore develop policy tools with the ambition that matches the scale of the challenge.

Over the coming weeks and months, the challenge policymakers in Scotland face is to find 100,000 additional opportunities for young people in Scotland for this next year. With summer coming to an end and the end of furlough approaching at the end of October, we only have a matter of weeks before the tidal wave of unemployment hits. If we are to avoid the lasting damage to our young people and to our economy that we’ve seen in the past, we will need to see employers, government, the college, school and university sectors urgently come together to protect as many young people as possible from the lasting damage of youth unemployment.

In our view this will need action on the following fronts to meet the scale of the ‘100,000 challenge’:

- Increases in college and university places – including a significant cohort of January-starts in the college sector

- Increased investment to protect and increase apprenticeship numbers in Scotland

- A large-scale and ambitious Scottish Jobs Guarantee – as called for by IPPR Scotland and announced by the Scottish government (with details to follow)

- Work between employers, trade unions and government to maximise access to the UK government’s Kickstarter Scheme, and to maximise jobs for young people through existing routes (such as the Developing Scotland’s Young Workforce and regional youth employment groupings).

- UK government should replace the furlough scheme with a short-time working scheme for sustainable jobs, which would see employers take back staff part-time rather than laying them off while the hardest-hit sectors recover.

- A UK government fiscal stimulus this autumn, with Scottish government budget decisions in turn prioritising fair, green and sustainable jobs and apprenticeships for young people.

By working with employers, employees and across the skills system, the UK and Scottish governments must find ways to find 100,000 new opportunities for young people in Scotland, across education, training and jobs, to minimise youth unemployment, and prevent a jobs crisis becoming a youth crisis in Scotland.

Notes:

Since late 2004, 18-24 year olds have made up around 30 per cent of the unemployed population across the UK including throughout the Great Recession (ONS 2020a) meaning changes to youth unemployment have occurred proportionally with changes in general unemployment historically.

On average around 8.5 per cent of the total youth unemployed caseload are resident in Scotland (though there has been some variation over that time - between around 12 per cent to 5 per cent) (ONS 2020b).

The assumptions underlying the 3 scenarios are as follows:

Scenario | Overall unemployment forecast | Youth impact relative to general impact | Scotland impact relative to UK impact |

Low | OBR – Upside Scenario | Proportionate as in previous recessions | Scotland sees 6.5 per cent of additional youth unemployment caseload |

Medium | OBR – Central Scenario | Proportionate as in previous recessions | Scotland sees 8.5 per cent of additional youth unemployment caseload |

High | OBR – Downside Scenario | Disproportionate – assume youth unemployment moves to 40 per cent of total caseload. | Scotland sees 10.5 per cent of additional youth unemployment caseload |

References:

Bank of England [BoE] (2020) ‘Monetary Policy Report – 2020’

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/monetary-policy-report/2020/may/monetary-policy-report-may-2020

HM Treasury [HMT] (2020) ‘Forecasts for the UK Economy – May 2020’ https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/forecasts-for-the-uk-economy-may-2020

Office for National Statistics [ONS] (2020a) ‘Table UNEM01: Unemployment by age and duration: People (seasonally adjusted)’, dataset https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/datasets/unemploymentbyageanddurationseasonallyadjustedunem01sa

Office for National Statistics [ONS] (2020b) ‘X02 Regional Labour Market: Estimates of unemployment by age’, dataset

https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/datasets/regionalunemploymentbyagex02/current

Office for National Statistics [ONS] (2020c) ‘LFS: Unemployed: UK: All: Aged 18-24: Thousands: SA’

https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/timeseries/ybvn/lms

Office for National Statistics [ONS] (2020d) ‘LFS: Unemployed: UK: All: Aged 16+: 000s: SA: Annual = 4 quarter average’ https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/timeseries/mgsc/unem

Office for Budget Responsibility [OBR] (2020) ‘Fiscal sustainability report – July 2020’ https://obr.uk/fsr/fiscal-sustainability-report-july-2020/

Resolution Foundation (2019) ‘The RF Earnings Outlook Quarterly Briefing: Q3 2018’ https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2019/04/RF-Earnings-Outlook-Briefing-Q3-2018.pdf

Related items

Who gets a good deal? Revealing public attitudes to transport in Great Britain

Transport isn’t working. That’s the message from the British public. This is especially true if you’re on a low income, disabled or living in the countryside. The cost of living crisis has exposed the shortcomings of our transport system,…

Bhargav Srinivasa Desikan on TalkTV discussing AI

IPPR's Bhargav Srinivasa Desikan on TalkTV discussing his new report on the impact of generative AI on the UK labour market.

Transformed by AI: How generative artificial intelligence could affect work in the UK – and how to manage it

Technological change is a good thing. It has brought exponential gains to living standards and is the foundation of modern society. Yet unmanaged technological change has always come with risks and disruptions.